While Jellicoe was DNO (February-August 1905), he came to the conclusion that British AP was unreliable at oblique angles – which would have been the case with gunnery at ranges over 10,000 yards.

The ordnance debate that Jutland launched should have happened at the start of the war, after the Battle of the Falklands and then Dogger Bank. Ernle Chatfield had commented:

There seemed no doubt that our gunners had not succeeded in hitting the enemy sufficiently, or if they had, then why had they not been put out of action? Were our projectiles the cause? But all the experts had faith in them.[1]

One was Churchill, who as First Lord praised British ordnance in the House of Commons:

Although the German shell is a most formidable instrument of destruction, the bursting, smashing power of the British projectile is decidedly greater.[1]

The facts of the time pointed to something different. The massively damaged Blücher had already had 60 heavy shells pumped into her but would not sink until torpedoed. Even the Seydlitz’s only main damage was from the turret hit. After the engagement, captured enemy officers spoke quite openly about the poor performance of British ordnance:

Twelve-inch shell seemed to go right through the ship without exploding in most cases.[1]

It was the same during the Falklands campaign. The German force ran out of ammunition. It took three hours to sink the Scharnhorst while the Gneisenau did not sink as a result of gunfire, even though she had received more than 50 hits. In the end she only sank because she was scuttled by her crew.

The truth is that Jellicoe had lobbied strongly – but ineffectively, as the cost was deemed too high – for more realistic trials of ammunition in October 1910, two months before he was transferred back to sea duties. Most British testing was done at long range, with plunging shells hitting deck armour rather than belt armour; so the effect of hitting at the oblique (i.e. with a shell that was steeply plunging down onto a target rather than being fired at a lesser angle and therefore closer to 90 degrees) was not highlighted.[1]

In July 1914, a mere few weeks before the outbreak of war, Jellicoe had delivered a pretty pessimistic report to Churchill, much to the latter’s displeasure. Maybe too much has been made by the British of the quality of ammunition used at Jutland.

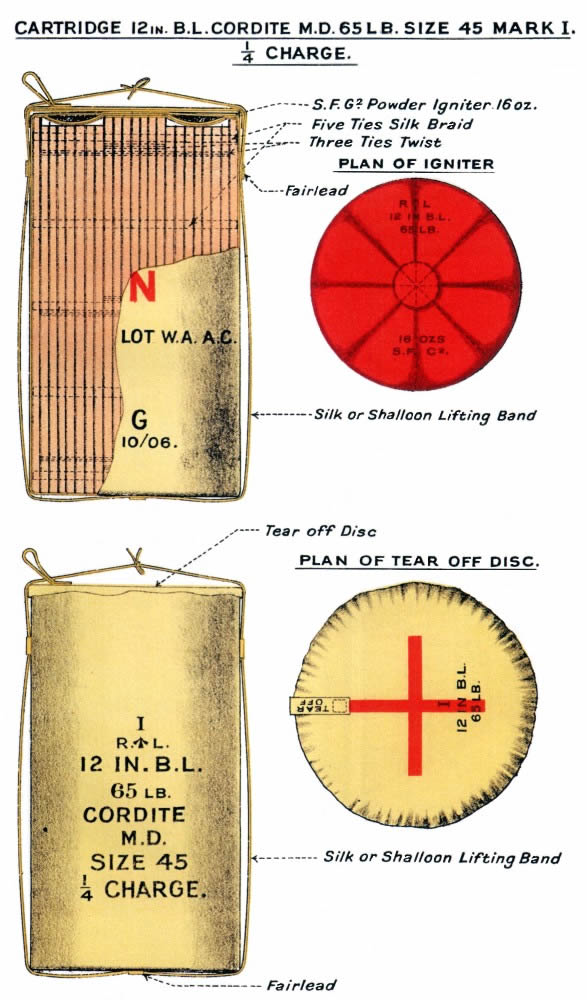

Blaming ordnance takes much of the focus away from gunnery and training. As stated, British cordite was dangerously unstable. Range performance could significantly differ by production batch. AP shells were propelled by a cordite charge, usually packed in four “quarter-charge” silk bags (noted above). German charges seem to have resulted in salvos often displaying much closer grouping.

Cartridge 12in. B.L. Cordite M.D. 65LB Size 45 Mark 1

The lack of reliability in performance of British cordite was compounded by the Lyddite used in the AP rounds as a “burster”. On surface impact these tended to detonate prematurely rather than within an enemy ship and, at oblique angles, the result was even worse.

By contrast, German shells used a more stable substance, Trotyl (TNT), and had a fuse system with far better time-delay characteristics, resulting in more internal explosions on British ships. The British AP shell known as a “Green” finally replaced the old shell (called a “Yellow”) that had been the cause of so much heated debate and finger pointing. But it was not introduced into the fleets till 1918, too late to make an impact.

The gunnery performance of the Grand Fleet was – during its limited engagement with the High Seas Fleet – demonstrably better than that of the 1st and 2nd Battle-Cruiser Squadrons but dismissed at the time. Dreyer calculated that with a better shell, the British could have expected to claim considerably more sinkings between 7.00 and 7.30 pm: “three or four battle cruisers and four or five battleships”.[1]

British ordnance left much to be desired. It was also easy to turn the discussion against Jellicoe. Beatty is said to have discovered how laughable the Germans supposedly thought British munitions were through the dinner remarks of a Swedish naval officer in August 1916.[1]