Nineteen hundred and six was a revolutionary point in the middle of the naval age of steam. HMS Dreadnought was launched; and in talking about the state of navies, the terms “pre-dreadnought” and “super-dreadnought” underline the importance of the moment.

The Dreadnought sacrificed armour for speed and broadside power. She was a weapons platform of eight 12-inch guns, each capable of hurling an 850-pound shell 17,990 yards across the sea while knifing through the water at 25 knots with her powerful Parsons turbines. These had replaced the mammoth reciprocating engines. The Dreadnought’s new Parsons had increased her speed from 16 knots to around 21; the increased speed came with decreased maintenance. A new weapons platform demanded improved gunnery; Admiral Percy Scott revolutionized naval gunnery, introducing training with moving targets, spotting and director firing.

The German fleet was primarily developed for short-distance operations and crews often slept ashore. Short ranges meant less fuel. Less fuel meant more space, with lighter guns and more armour or armament weight. German ships tended to be lighter-gunned, slower but far more heavily armoured as a ratio to total displacement.

Here are some examples:

- Iron Duke: 25,000 tons displacement; maximum side armour 12 inches; maximum turret armour 11 inches.

- König: 25,390 tons displacement; maximum side armour 14 inches; maximum turret armour 14 inches.

- Lion: 26,350 tons displacement; maximum side armour 9 inches; maximum turret armour 9 inches.

Another way of looking at it is to compare total armour to armour:

- Queen Mary: 27,000 tons displacement, of which 3,900 tons was armour.

- Seydlitz: 24,600 tons displacement, of which 5,200 tons was armour.

Even coaling spaces were used very effectively for increased protection. When they inspected many German ships at Scapa Flow straight after the end of the war, British commentators saw for themselves their strength of construction: the Lützow limped back with 5,300 tons of water on board; the Derfflinger with 3,000 tons. Quoting an officer inspecting the Friedrich der Große, Richard Hough was told:

What impressed me most was the honeycomb of small boiler rooms, all in completely separate watertight compartments, whereas our boiler rooms were vast compartments stretching athwart the ship. Again, I was impressed by the use of coal bunkers to add protection to the side armour.

No wonder they lost some speed. One certainly got the impression she would have been the very devil to sink.[1]

German ships were broader beamed, allowing more side armour as well as superior performance as a stable gun platform.

Here are some examples of beam:

- Iron Duke: 90 feet.

- König: 97 feet.

- Lion: 88 feet.

- Derfflinger: 95 feet.

The broader German beam came about because the British did not invest in the prize tool that was Britain’s protection against trade war: its navy. In this particular instance, the issue was to update dry-dock facilities.

Jellicoe and Beatty differed in their individual appreciation of the strength of British ships. Jellicoe declared in 1914 that “it is highly dangerous to consider that our ships as a whole are superior or even equal fighting machines” to those of the new German navy,[1] while Beatty’s famous aside on the bridge of the Lion to Chatfield, that something was “wrong with our bloody ships today”, suggested that this realization only came later.

In the same way, Nelson at Trafalgar had supreme confidence in his ships. He knew that at close quarters the Spanish and French ships would be no match for his. For Jellicoe, it was different. He was technically exceptionally knowledgeable about ship construction and had seen much of the German materiel up close. He was under no illusion about the superiority of British ship design. He also knew where the weaknesses were.

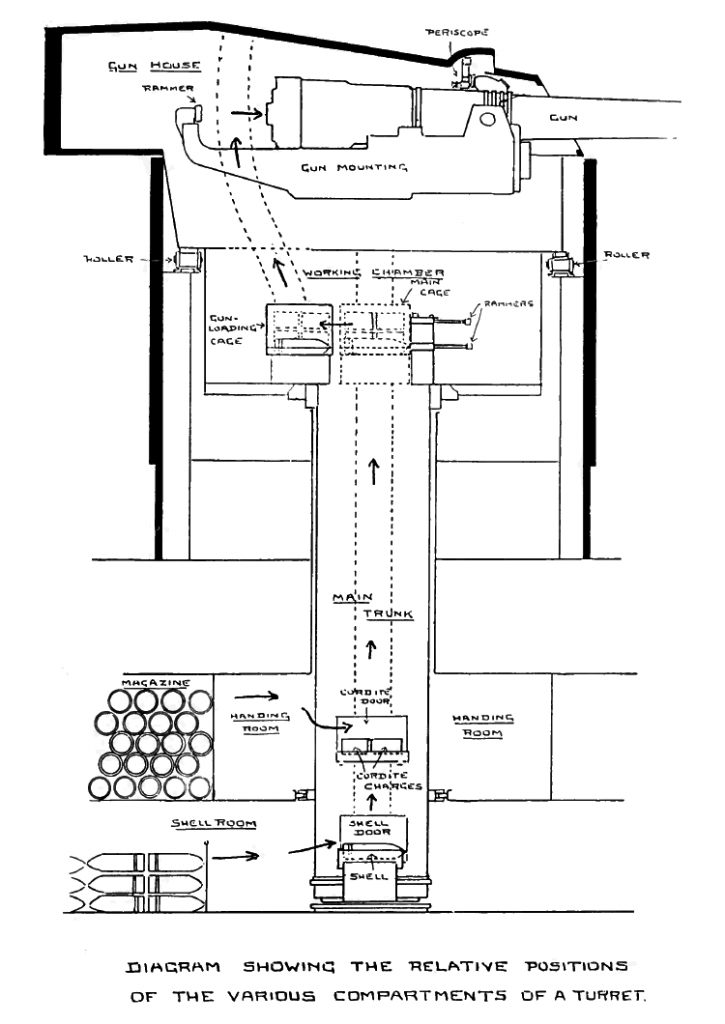

Magazine Protection: Anti-Flash

The dangerous practice of stacking ammunition outside of the protective magazines and even leaving anti-flash doors open during battle was a direct result of a British obsession with speed of gunnery. It might be no coincidence that the ships that were considered to have the fastest gunners in the British navy were the Invincible and the Queen Mary, ripped apart by horrendous magazine explosions and each going down with almost all hands. Of the 6,094 British sailors who lost their lives at Jutland, 38% – 2,292 hands – were from these two ships alone. Add in the 1,017 deaths from the sinking of the Indefatigable and more than half the deaths at Jutland resulted, in part at least, from this tragic belief in gunnery speed and also from the over-confidence in British battleship design.

Fawcett and Hooper, p.95

It was always suspected that the system of anti-flash doors would be compromised by an obsession with speed. Confirmed by divers’ inspections of the wrecks of the Queen Mary, the Invincible and the Indefatigable later in the century was that the silk cordite bags were brought up from the magazines and stacked in the passageways below the guns. British cordite was not stable and actually became even less so with age. The silk bags in which it was packed caught fire easily.

German charges, by contrast, were stored in expensive, machined brass tubes and quite different to the British. The Germans had taken what they learnt at Dogger Bank in 1915 and applied it quickly. The British paid for their lack of learning with the loss of three capital ships. The Germans, on the other hand, were quick to apply the learning that they had gleaned from the near-death experience that the Seydlitz had had at Dogger Bank; 120 men were killed in a turret’s explosion but the magazine had not been similarly ignited. After the battle the Germans immediately tightened up. Stacking propellant in the turret was limited and anti-flash doors were redesigned.

For the Germans, protection of the magazines was a priority while mainly ignored on many British ships, especially in the Battle-Cruiser Fleet. Beatty was very quiet about this as a possible factor in the brutal battle-cruiser losses but his Battle-Cruiser Battle Orders (BCBOs) were changed.

HMS Lion hit on Q turret.Destroyers taking up position in van to attack.

His own near-death experience on the Lion no doubt added a new perspective and, ironically, Beatty owes much to his chief gunnery officer, A.C. Grant, who had been brought up in the practices of the Grand Fleet and had actively limited the open stacking of cordite against considerable opposition.

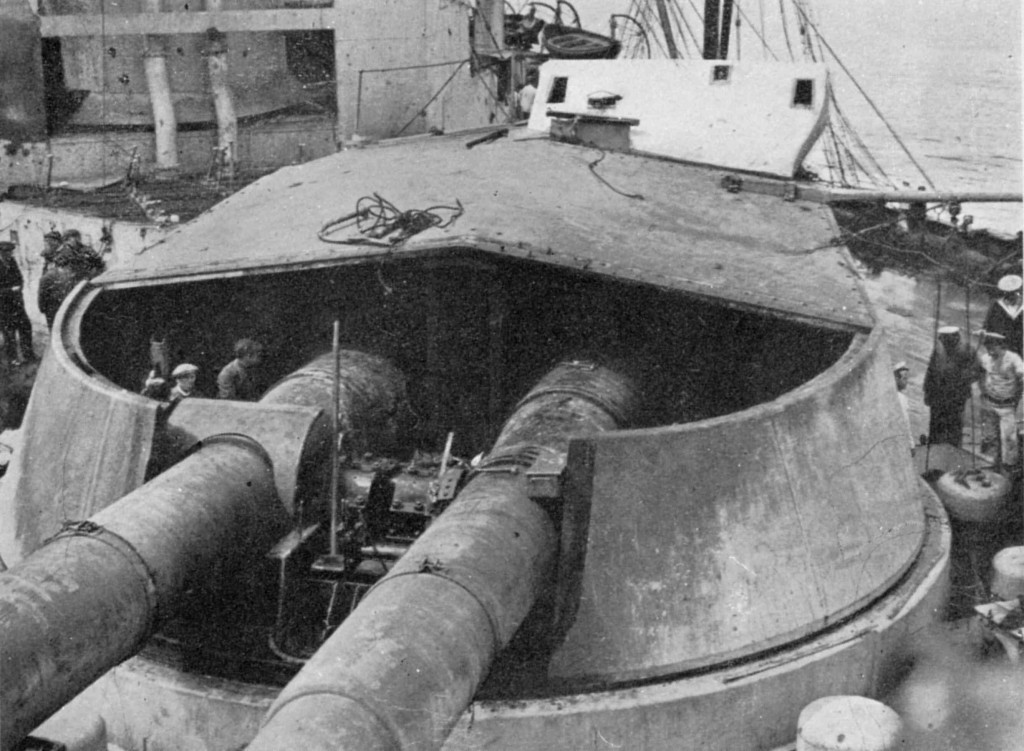

Damage to Q turret of British battle cruiser HMS Lion after the Battle of Jutland . Front armor plate has been removed.

Lion’s Q turret. The ship was saved when the turret top blew off. There were heavy casualties (98 died in the turret) but the ship was saved by the explosion being allowed “out in the open”

Lion’s Q turret