Before 1914, British naval thinking was that the Germans would want to fight a medium-range battle in which they could maximise their gunnery and torpedo assets. Early actions in the Falkands campaign confirmed German capability in this. In December 1914, intelligence from German gunnery practices[1] was received. It was immediately distributed to the fleet commanders.

Quoting from German Tactical Orders, Matthew Seligmann underlines the nervousness over a short-range battle that existed in the German navy: “A long- range action at great ranges is not to our advantage. We must on the other hand attempt to get as soon as possible within ranges from 8,800 to 6,600 yards to make use of our strong medium-calibre armament and our torpedoes”.[1]

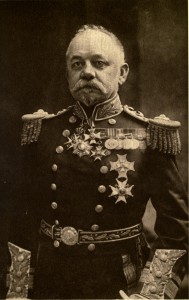

Admiral Sir Percy Scott (1853-1924)

Admiral Sir Percy Scott (1853-1924) revolutionised gunnery in the Royal Navy introducing disciplined range-finding and extending gunnery ranges. (Photo : Rogers, The New York Times Current History : The European War (April – June 1915, Vol. 3)

Seligmann and Jon Tetsuro Sumida differ on a major point: whether officers in the Grand Fleet believed this information. Seligmann: “Revealingly, however, it seems that those in charge of the Grand Fleet did not believe it…”. [1] Sumida: “Dreyer, and undoubtedly Jellicoe as well as others, believed this information to be sound”.[1] Seligmann points out that the same document stated that a longer range duel was quite possible: “There are no reasons for us to open fire at ranges over 13,200 yards, unless the enemy should force us to open before, by himself opening fire at greater ranges”. [1]

Sumida maintains that the British changed their tactics around 1912 and developed an approach based on closing to 10,000 yards to effect a powerful five- minute bombardment of their foe and then turning to avoid the inevitable, multiple bubble tracks of a German torpedo attack.[1] He attributes this tactic, which he called the “Technical-Tactical Synthesis”, to Jellicoe himself knowing that if the Germans fought a medium-range battle (one within 10,000 yards) the enemy fleet would have the advantage of being able to add to its heavy guns – substantial secondary armament as well as all their torpedo assets. Matthew Seligmann disputes Sumida’s view, saying that despite the appeal of such an argument “the evidence marshalled in favour of this assertion is at the very least questionable”. He holds “that in this very period the British naval authorities actually began to consider the very opposite idea” – in other words, that the Germans preferred a longer-range action.[1]

Seligmann supports this with a number of facts: the first is from a Naval Intelligence publication, ID973, which specifically stated that there was practice (albeit with fairly poor results) above 10,000 yards. However, data from later practice shoots in April 1913 show considerably improved longer range-gunnery performance.

The Admiralty data sent to Jellicoe report on German gunnery practices in 1913 and 1914, from which Jellicoe assumed that, because secondary armament was firing at the same time as the principal guns, “the range did not exceed 8,000 yards” [1]; it was shown by the ID973 data that secondary armament could very effectively be used at ranges of up to 13,000 yards.

Reports right at the start of the war – from the Falklands campaign – brought back important intelligence about German long-range gunnery. According to Vice-Admiral Sturdee, on the Invincible, “Following experiences gained in recent action. German 8-inch guns reach 16,000 yards, straddled ship(s) at 15,000 yards, 6-inch and 4-inch guns effective at 12,000 yards, [the] latter outranging Kent’s 6-inch guns”. In fact, Sturdee reported that the Germans had managed to land 83 hits on the British.

Boys in training at Shotley Barracks on 6 inch battery work. (Author’s Collection)

Behind the gunnery debate was the threat of the torpedo and how fast it was developing. In two years the range of the typical British torpedo had more than doubled from 5,000 to 12,000 yards.[1] It was not just the range vulnerability, it was the statistically underlined threat that a spread of torpedoes would have on a battle line.

This is how the talk of divisional manoeuvre started. Even if “theoretically the divisional attack may seem simple enough” it was “much more difficult in practice” (Sumida in “A Matter of Timing…”.[1]) Breaking up the line would, of course, have added significant difficulty to gunnery, itself creating the need for mechanical plotting that could integrate course changes into its workings. Arthur Pollen was thus asked by Captain Frederick Ogilvy to develop such a “helm- free”[1] system. Ogilvy died in 1909, having achieved the fleet gunnery record, but his fear of torpedo attack on a line of battleships was echoed by Battenberg and Churchill.

Some of Pollen’s work started to be used on board battleships – for example, the gyroscopically stabilised range-finder mount which “increased the rate of range-taking by a factor of five”. Added to Pollen’s work was Frederick Dreyer’s system of fire control (FC), a system that recorded ranges and then averaged them to increase reliability. After Pollen combined his FC system with “a range-generating machine”, it was taken on by the Admiralty for reasons of cost over what many still believe to have been the superior system: Pollen’s Argo Clock, only added to Dreyer’s Table (as his system came to be known) in a few cases.

Sumida says that Jellicoe changed his tactics in around 1912 after finding “serious command and control problems” with gunnery and manoeuvre using divisional tactics and employing Percy Scott’s director system, Dreyer’s Table and Pollen Argo Clock.[1] Combining gunnery power and the torpedo threat, the British, Sumida argues, developed the idea of a short, very intense bombardment of the enemy line before a turn-away timed to coincide with the torpedo’s arrival at its line. Given that at 30 knots 7,000 yards could be covered in seven minutes and 10,000 yards in around 10 minutes, leaving two minutes to execute the turn- away manoeuvre, this gave the British between five and eight minutes gunnery time from the battle line. Jellicoe decided to push the limit out from a medium- range initial engagement to a longer-range engagement and, with each successive year, in his orders one sees him steadily pushing this outer limit further away from the British battle line.

At the same time Jellicoe knew from his time as DNO that British armour piercing (AP) was ineffective over 10,000 yards, as the shell hit at an angle higher than 20 degrees. To my mind, then, he considered that these outer limits of range were for zeroing-in on and destroying enemy superstructure, while the really destructive AP fire would start below 10,000 yards; given that the GFBOs in force on the eve of Jutland talked about fire being opened between 10,000 and 15,000 yards in good weather and up to 18,000 yards should the Germans open fire, I tend to agree.

Captain Hopwood, Lieut.Buxton. John Rushworth Jellicoe, Mr Share, Commander Dreyer

Admiral Sir Frederic Charles Dreyer (1878 – 1956) was Jellicoe’s Flag Captain at Jutland and an acknowleged expert on gunnery and fire control. He is seen here in a group photograph with Jellicoe (From left to right : Captain Hopwood, Lieut.Buxton. John Rushworth Jellicoe, Mr Share, Commander Dreyer). (Photo : author’s collection).

A 31 August 1914 addendum to the first set of GFBOs, released on the 11th, stated: “on a clear day and unless the enemy opens fire earlier, 13.5-inch-gun ships will open deliberate [my italics] fire at 15,000 yards, 12-inch … at 13,000 yards … At extreme range fire should be deliberate salvos until the enemy is hit or straddled … ships should not employ rapid fire at ranges over 10,000 yards [my italics]”. In the Commander-in-Chief’s opinion, “close action is to the German advantage”. Sounding a death knell to the divisional school, he explained that “action on parallel course is one of the underlying objects of my tactics … because it is the form of action likely to give the most decisive results”.[1]

The later GFBOs pushed the limits of engagement out. The December 1915 orders stated that Jellicoe did not “desire to close the range much inside of 14,000 yards … Until the enemy is beaten by gunfire it is not my intention to risk attack by torpedoes”. He made it clear that “we must gradually close the range to obtain decisive results”.

Jellicoe made no mention of the so-called turn-away after an intense bombardment. Sumida holds this up as a need for secrecy. Jellicoe talked openly in the last set of orders before the battle (26 May 1916). “In all cases the ruling principle is that the dreadnought fleet as a whole keeps together, attempted attacks by a division or squadron on a portion of the enemy line being avoided as liable to lead to isolation of the ships which attempt the movement … so long as the fleets are engaged on approximately similar courses, the squadrons should form one line of battle”.

While the German navy generally tended to be lower calibered, this was more than made up for in the effectiveness of its shell and the accuracy of its firing. Because of the superior steel, the smaller calibered German turrets were considerably lighter than their British counterparts and the additional weight put into armour instead.

Battle Range and Shell Effectiveness

In October 1910 Jellicoe requested that the Ordnance Board “produce designs of AP shells for guns 12 inches and above which at oblique angle would perforate thick armour plate in a fit state for bursting”.[1] His request came on the back of disturbingly unsuccessful gunnery trials using HMS Edinburgh as a test target. Lyddite AP shells broke up on the belt armour at angles greater than 20 degrees. Meanwhile, reports from French gunnery trials were showing that their nickel-chrome steel AP shell was successfully breaking through the armour layer and bursting inside.

Two months later, in December 1910, Jellicoe was posted to the Atlantic Fleet on the Prince of Wales. His successor, Admiral Sir Charles Briggs, “the old sheep farmer” as Fisher called him, did not pursue the issue with any great sense of urgency.[1] Iain McCallum’s point of view, however, is that the Ordnance Board’s decision to stay with Lyddite rather than use TNT meant that a superior shell solution was impossible; furthermore, orders for Lyddite HE and AP had already been placed. With the likely cost of AP being three times that of Common (a designation used for shell with a low explosive mixture), the board was even more inclined to try to improve the existing shell rather than design a completely new one.