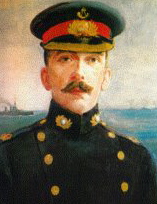

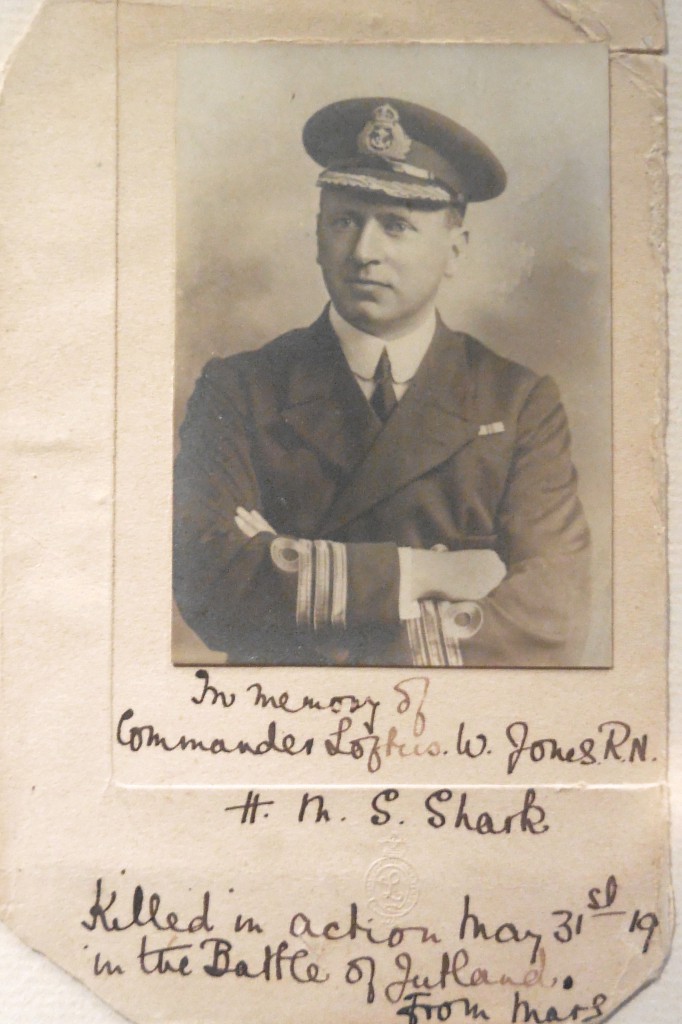

Commander Barry Bingham

The son of Lord Clanmorris, Edward Bingam joined the Royal Navy in 1895. By the time of Jutland he was a Destroyer Flotilla commander working closely with Vice Admiral Sir David Beatty’s battle-cruisers.

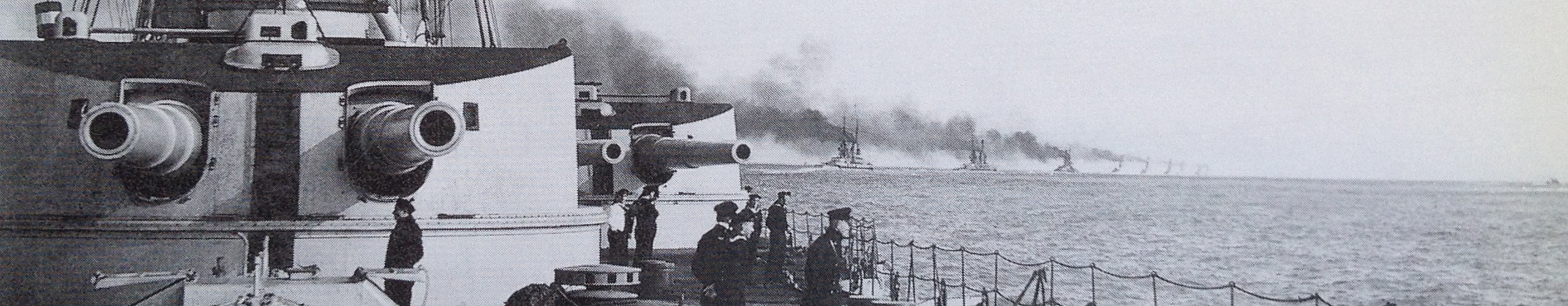

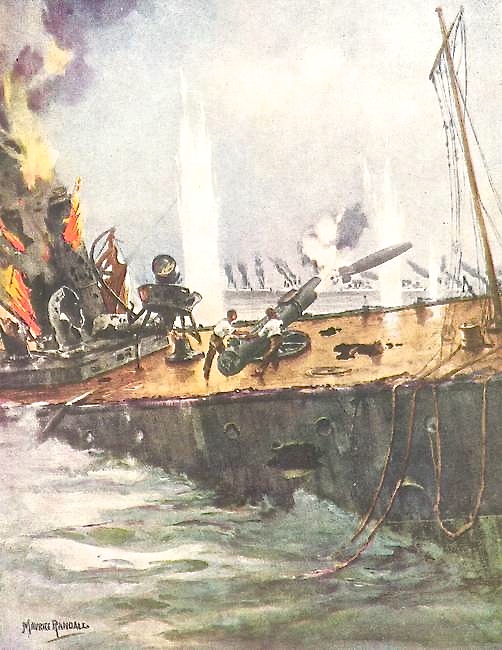

At a round 16 :15 – around twenty five minutes after the battle-cruiser struggle had begun – Beatty ordered the destroyers to attack the German line. At almost the same Lion scored a hit on Lützow, Captain James Farie, the 13th Flotilla commander, relayed Beatty’s orders that had come through from Champion to the flotilla under the command of Nestor’s captain, Barry Bingham Beatty believed the role of the destroyer was to attack the enemy battle line rather than wait defensively for a German torpedo attack as Jellicoe was inclined.

round 16 :15 – around twenty five minutes after the battle-cruiser struggle had begun – Beatty ordered the destroyers to attack the German line. At almost the same Lion scored a hit on Lützow, Captain James Farie, the 13th Flotilla commander, relayed Beatty’s orders that had come through from Champion to the flotilla under the command of Nestor’s captain, Barry Bingham Beatty believed the role of the destroyer was to attack the enemy battle line rather than wait defensively for a German torpedo attack as Jellicoe was inclined.

First, Bingham continued southwards hoping to gain a better position.Then across the gap between the opposing battle lines. Almost immediately Nestor, Nomad and Nicator were cut off from the rest of the group when one of the 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron, Nottingham, cut through the destroyer line, obliging the Petard to take immediate and violent evasive action. Which had the effect of breaking up the attack. The leading group of five went on but eventually Narborough and Pelican doubled back to join Champion.

Bingham turned his destroyer, Nestor, along with one other destroyer from the Flotilla, HMS Nicator, to attack Hipper’s battle-cruiser aline.

Together reached to within about 3,500 yards of what turned out to be Lützow. Each fired two torpedoes, but after all their efforts, neither was lucky enough to score a single hit. They then made a second run, getting in a little closer.

Bingham even managed to get off a third torpedo and the two boats turned 180 degrees and headed west back towards the British lines which at least for the battle-cruisers, were steaming back north, making Hipper think that he had them on

the run.

At this point – it was about 17:00 – Nestor was hit twice from a range of around 3,000 yards (2,700m), but it is not known whether this was from the Regensburg or from one of the battle-cruisers in the van (the head of the line). Her boilers badly damaged, Nestor still managed to steam a further four miles, but half an hour later stopped not far from Nomad.

The Nicator swung back to try to help Bingham but was bravely waved off by the young Irishman.

His ship was badly damaged and sinking. He waved off help offered from

HMS Nicator. The Nestor continued sinking. Bingham was picked up and became a prisoner of war spending the rest of the war in an officer’s POW camp at Holzminden in Lower Saxony. He went back to active service in the Navy and retired sixteen years after Jutland as a Rear Admiral. Seven years later he died.

HMS Nicator. The Nestor continued sinking. Bingham was picked up and became a prisoner of war spending the rest of the war in an officer’s POW camp at Holzminden in Lower Saxony. He went back to active service in the Navy and retired sixteen years after Jutland as a Rear Admiral. Seven years later he died.

The citation on his VC reads:

For the extremely gallant way in which he led his division in their attack, first on enemy destroyers and then on their battlecruisers. He finally sighted the enemy battle-fleet, and, followed by the one remaining destroyer of his division (Nicator), with dauntless courage he closed to within 3,000 yards of the enemy in order to attain a favourable position for firing the torpedoes. While making this attack, Nestor and Nicator were under conce

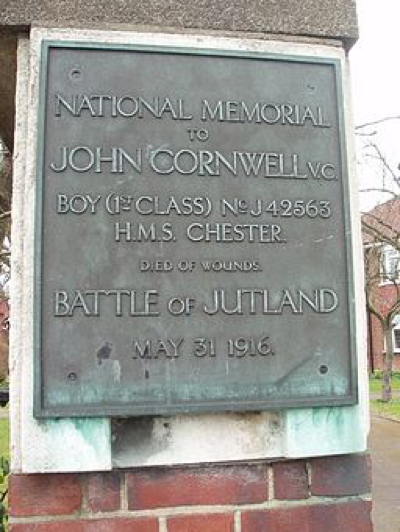

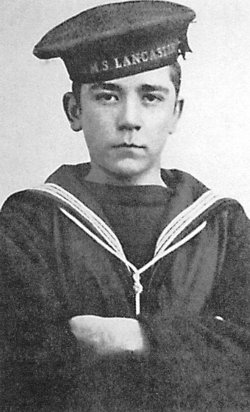

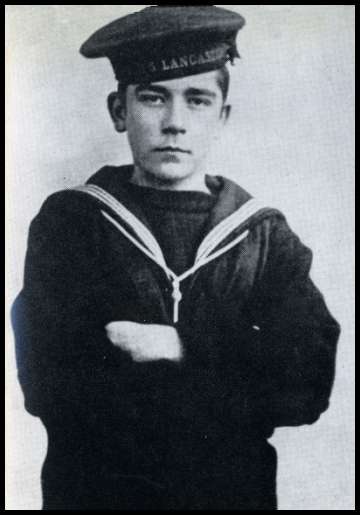

Boy First Class Jack Cornwell

John Travers Cornwell was a London boy. He was born in Leyton, North London on January 8th 1900. His father, Eil, had been in the forces and had served in Egypt and South Africa in the RAMC. Aged ten, the family came to Manor Park where they lived at 10, Alverstone Road and Jack discovered the first love of his life. Scouting. He joined the St Mary’s Mission,Little Ilford. Hi schooling continued at the Walton Road School. It is now known as the Cornwell School.

Before he joined the Navy, the young 15 year old Jack Cornwell was working as a Bicycle delivery boy. When he did enlist, he went without his father, Eli’s, permission. From August 1915 to May 1st 1916, his initial training was in Deveport on HMS Vivid He did well and and scored 84% in gunnery and was judged to have a « very good » character.

On May 2nd he joined the newly commission light cruiser, HMS Chester, as a gun layer. Twenty nine days later he would be at sea in the battle that claimed his life.

A gun layer’s job was to relay the officer’s orders to the gunners.

When the Chester was caught by some of Bödicker’s scout ships, Chester came under a rain of fire and was hit 17 or 18 times. The carnage was terrible.She’d originally been built for (and therefore to) Greek Navy specifications. One of the reasons why there were so many casualties was because there was a gap between the armoured protection over the guns and the decks. Shrapnel scythed through this gap and caused terrible leg injuries, in many cases severing feet. At Cornwell’s gun, forward on the Chester, all the crew except two were either killed or critically injured. As was Boy Cornwell.

He stayed by his gun but it was clear that he would not last. He died on June 2nd in a hospital in Grimsby. He was buried in a common grave on June 8th. A simple number marked the spot. His Captain wrote to Jack’s mother saying that he had written to the Admiral about her son’s extraordinary courage under fire and inviting her to come and see the mess plates that he had had made with Jack’s name on it.

I cannot express to you my admiration of the son you have lost from this world. No other comfort would I attempt to give to the mother of so brave a lad, but to assure her of what he was and what he did, and what an example he gave.

When Admiral Sir John Jellicoe wrote his Official Despatches he also recommended further recognition be given Cornwell’s actions but it was later that summer when Lord Charles Beresford, who had read the after-action reports, recommended that Jack Cornwell’s quiet, determined courage be recognized in awarding him a posthumous Victoria Cross. The eventual citation reads :

Mortally wounded early in the action, Boy, First Class, John Travers Cornwell remained standing alone at a most exposed post, quietly awaiting orders, until the end of the action, with the gun’s crew dead and wounded all round him. His age was under sixteen and a half years.

Cornwell had been a Boy Scout and it was not unnatural that, in the same way he became a beacon of inspiration to the nation, he also became a legend in the Scouting community.

Most of the photos that claim to be Jack Cornwell are, in fact, his brother. Apart from anything else the cap tally keeps on changing. You never se one (or I haven’t) with HMS Chester. You do see (as above) HMS Vivid.

On 29th July 1916 Jack Cornwell was finally re-buried with full military honours at Manor Park Cemetery. Fellow Boy sailors from his old ship acted as the Honour Guard. Eli died later in 1916 and, along with Jack’s brother, Arthur, were all buried alongside the young hero.

In July a Jack Cornwell Memorial Committee was also set up and later in 1921 its charity recommended building cottages for ex-sailors in Hornchurch and they were officially opened by Admiral Jellicoe on 31st May 1929.