The story of one man giving his life so another could live

Algernon William Percy, known as Bobby, joined the Royal Naval Reserve as a sub-lieutenant on the outbreak of war at the age of 29. He had wanted to join the army, given his eight years’ service with a Militia battalion in the Northumberland Fusiliers, from which he retired with the rank of lieutenant in 1910. But his poor health would not stand up to the rigours of front line military duty and his position in the Northumberland Fusiliers had largely been due to his family’s association with the regiment: his uncle was the 7th Duke of Northumberland, and his father, Lord Algernon Percy, was Lieutenant-Colonel commanding the battalion. Bobby was educated at his parents’s home, Guy’s Cliffe, Warwickshire because his health was too delicate to allow him so be sent away to boarding school. His first formal education came when he went up to Christ Church in 1904, following in the footsteps of many relations over the years.

As he was nearly 20 when he went to Oxford, he remained there for only one year. After that, he was a Justice of the Peace and a County Councillor in Warwickshire – where he also served on the Prison Visiting Committee and the Hospitals Committee. Outside of officialdom, he was well known and popular on the hunting field.

When he secured a place in the Royal Naval Reserve, he was delighted – all the more so to be aboard a vessel at Spithead by 24th September 1914. He wrote to his uncle, the Duke, “I am looking forward to it very much…it is a thoroughly well thought out scheme so I don’t think I was wrong in taking it as I couldn’t have got anything else I could have managed half so well, and I couldn’t sit at home doing nothing.” He added that he felt very lucky, and pleased that his parents were quite willing for him to go. The family did not have a recent tradition of serving at sea: Bobby’s father, like so many Percies, had served in the Grenadier Guards and his great uncle (Lord Henry Percy, also a member of the Travellers Club) had won a Victoria Cross with the same regiment at the Battle of Inkerman in 1854. However, Bobby’s great-grandfather’s generation included three admirals: Jocelyn and William Percy had served as junior officers in the Napoleonic wars – as had their cousin, the 4th Duke of Northumberland, who eventually became First Lord of the Admiralty and president of the RNLI. As a cabinet minister in the 1850s, the 4th Duke played a part in accelerating the introduction of steam power to the Royal Navy.

Bobby’s first ship was the Royal Yacht Squadron’s Catania, a fabulously luxurious steam yacht belonging to the Duke of Sutherland which had recently been requisitioned by the Admiralty for minesweeping and U-Boat patrol in the Solent. He described it as “most comfortable…but by no manner of means a hazardous expedition.” That said, he was quick to tell his uncle that they had some guns (two 6-pounders) and lots of rifles and revolvers. But it was unlikely they would see serious action.

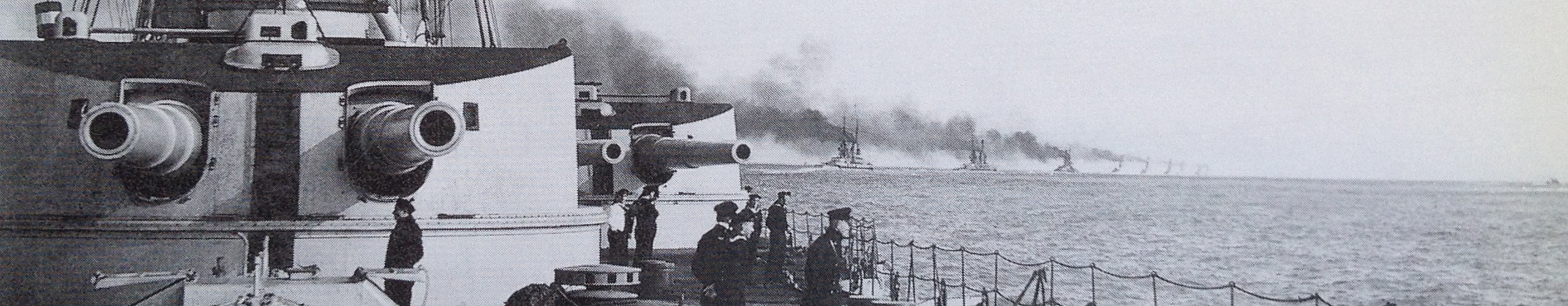

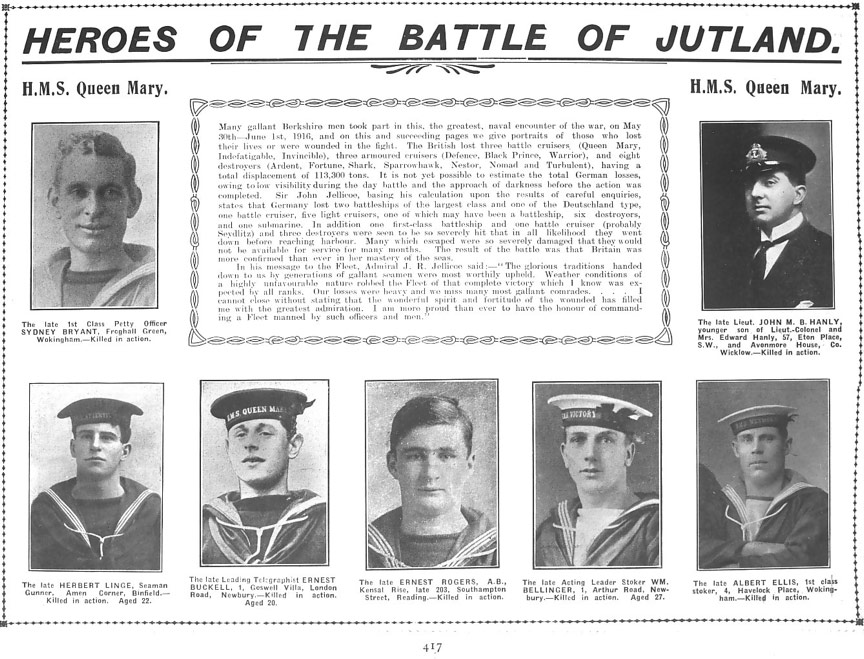

In January 1915 Bobby transferred to HMS Queen Mary. It was a prime posting for an aspiring naval officer, being one of the most modern ships in the service. Completed in 1913, she was a battlecruiser (i.e. fast and lightly armoured), and therefore designed specifically for offensive action. Her eight 13.5 inch guns had already come in to play at the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914. Bobby’s career aboard Queen Mary was interrupted by illness. He had to be hospitalized, and then spent considerable time on sick leave. It wasn’t until Monday 29th May 1916 that he was able to rejoin his ship – two days before the Battle of Jutland. Unfortunately, in an extraordinarily intensive action during the afternoon of Wednesday 31st May, the British battlecruisers bore the brunt of German firepower. Whereas less than 10% of British ships present at Jutland sunk, a third of the battlecruisers (three out of nine) were lost. Their relatively light armour, particularly on deck and near the gun turrets, was their undoing. Terrifyingly, all three exploded – their magazines hit – and sank in seconds, killing a total of over 3,300 men. Less than one per cent of the three battlecruisers’ collective crews lived.

Bobby actually survived the blowing up of HMS Queen Mary. After the initial explosion, which broke the ship in two, he found himself unhurt in the water; somehow, he had managed to get hold of a life jacket. A short time after, there was a second explosion which shook the aft end of the ship as it began to roll over and sink. He was wounded slightly in the forehead by a flying splinter – but, according to a surviving officer who was with him, he was “quite alright.” A destroyer soon appeared to pick them up, but about fifteen swimmers, including Bobby, were missed. The survivor, who wrote to Bobby’s father from a German prisoner of war camp a few weeks after the action, said that when they had all become cold and affected by the oil fumes all around them, Bobby offered him his life jacket, “for which action I shall never forget him, although I had only known him a few days.” Some time afterwards a German destroyer picked the man up, semiconscious. Only one able seaman was with him; the captain of the destroyer could see no more survivors and Bobby was never seen alive again. Just 18 of Queen Mary‘s crew of 1,264 lived.

A few weeks later, Bobby’s body was washed up with many others near Fredrikstad in Norway. An English lady living nearby attended a military funeral on 28th June:

“Another English lady and myself were the only ones of their own present, and as we stood by the graves we felt we were representing the mothers and wives of the brave men whose bodies we committed to the dust….

All the coffins were covered with the most beautiful wreaths and flowers brought by all kinds of people. Wasn’t it kind? All the bodies had lifebelts on but no discs with their names…. One officer had a ring with the initials A.W.P. and a crest engraved on his gold cuff buttons…. How I wished their friends could have known that the dear remains were laid carefully and kindly in consecrated soil, it would be a little comfort to their sore hearts.”

By a fortunate coincidence the author of that letter’s niece lived in Northumberland, and so Lady Algernon Percy discovered the details of her son’s burial.

A senior naval officer wrote:

“He had such a gallant big heart, always battling against delicate health and never flinching from anything because of it.”

Another wrote:

“His character was one of transparent truthfulness and honesty; he honestly was one of those not very common men who are absolutely incapable of a dishonourable action, and thus did us all no end of good by simply living with us.”

And a friend,

“He was the soul of honour and chivalry”

(Courtesy of Algernon Percy)

The horrifying newspaper list of all those fallen, HMS Queen Mary

A lucky Escape

Frederick John Chapman Cox was serving on HMS Queen Mary in early 1916. Six weeks before the battle he was transferred to HMS Princess Royal as a shipwright. There, while he was leading a damage control party on the upper deck, he witnessed his old ship and all his old shipmates blown up.

(Courtesy of Graham Chadwick. Frederick John Chapman Cox was his maternal grandfather)

Never knowing his father

Charles Albert Birks was the only child of Annie Elizabeth Birks. He was born on 8th April 1894 in Hull and was living at 91 Arundell Street, Hull. At the age of 16, the 1911 census shows he was a dock worker in Hull.

Aged nineteen, Charles joined the Navy.On 29th August 1913, beginning his naval career at Victory ll, service number SS / 114538 . He then served aboard HMS Vindictive from January to July 1914. It was during this service aboard Vindictive he married Ruth Gurnell in the April of 1914 and sent a post card around this time to Ruth depicting an image and poem called “The Sailors Grave”. On the back he wrote “Dear Ruth, I hope this will never happen to me, keep this one will you”. This poignant message to his new wife, unbeknown to her, held such meaning. His career then took him back to Victory ll for a month and then onto HMS Drake 1st Aug 1914 – 7th April 1915 During this service, Charles spent 10 days in the cells. As part of his punishment, he served aboard SS Alsatian, as there is a letter he sent to his wife Ruth on 25th December 1914. Charles was promoted to Stoker 1st Class on 4th April 1915. He then spent April to October 1915 back at Victory ll.

Charles Albert Birks, HMS Queen Mary

The day after Charles began his service on Queen Mary, his son, James Charles, was born 27th October 1915. During February 1916, Charles had a short leave period home. This was his only time with his new born son. He had travelled home on leave with a close friend, Stoker 1st class Jack Wilson, returning back to his duties at the beginning of March 1916. Charles Albert Birks was killed in action, age 22 on May 31st at Jutland.

(With kind permission of Michael Birks)

A seaman’s grave

Able Seaman Frederick Richard Sell was born in Bexleyheath on the 19th July 1894, one of nine children. He attended Foster’s School and when he started on 21st January 1901, the family were living at 1 Danson Cottages,

His parents had married at the end of 1886, his mother Minnee Jane (née Smith) born in Wilmington and his father, Richard, born in Reading. Richard was a domestic gardener and the family moved frequently with his work, the children being born around the borough: Amelia Temple born (1887, Crayford), Florence Emily A (1889, Bexleyheath), Alfred Harry (1891, Lee), Frederick Richard (19 July 1894, Bexleyheath), Ernest George (1st May 1898, Bexley), Olive Minnie (1901, Welling), Edith Mary (1903, Welling), Charles Victor (1906, Bexleyheath) and William Patrick (1908, Bexleyheath). The family’s Welling homes included Danson Lane and 3 High Street, Welling.

By 1911 Frederick had moved with his family to 7 Medina Terrace, Godstone Road, Whyleleafe. He was 17 years old and employed as a domestic post boy. His sisters Amelia and Florence had by then left home (Florence had married in 1909). and brother Alfred was living at 12 High Street, Welling, with his grand-father Isaac Smith.

Frederick joined the Royal Navy and by 1916 was an Able Seaman, service number J15717 serving aboard HMS Queen Mary.

Frederick died at sea aged 22 and his body was not recovered. In 1991 the wreck of the ship was discovered. The wreck site is now a designated protected place under the Protection of Military Remains Act 1986. No one can explore or remove items from the wreck although the propellers made of phosphor bronze may have been removed before 1991.

Frederick is remembered at the Portsmouth Naval Memorial and on the Welling War Memorial. Frederick’s death was notified to his mother who was then living at 1 Home Cottages, Godstone Road, Kenley, Surrey, near to where the Family had lived in 1911.

In a 1920 Jenkins local directory, the father, Richard is listed as living back in Welling – at 12 High Street. In 1921, Alfred Harry married Lily Ashdown. Their first child born in 1922 was named Frederick, probably in memory of his younger brother.

The ones who could never get out. The stokers.

Enos George Farr married Ada Saigeman in 1912. Together they had one child named after Enos’s father. Enos was a stoker on the Queen Mary and after his death, even though Ada married again twice, it was always Enos whom she mourned for all her life.

Enos George Farr (Queen Mary) and Ada Saigeman on their wedding day, 1912.

He is always remembered on the memorial at Bear Wood in Wokingham, Berkshire.

Times were hard and their son, “Tids”, ended up on the training ship Arethusa. Enos George Snr. was a Stoker on Queen Mary so was trapped deep inside the ship.

(Courtesy of Ann Churchett, grand daughter of Ada Saigeman)

Joseph Baker (286450) was another one trapped inside the deep hull of the Queen. The story of this Acting Chief Stoker will soon be told by his grandson who is coming over from Australia for the centenary and will be Portsmouth for the commemorations.

(Courtesy of Teresa Walker, grand daughter of Joseph Baker)

SOME MORE STORIES :

Imperial War Museum HMS Queen Mary community :

https://livesofthefirstworldwar.org/community/609