The story of two brothers who fought in the biggest naval battle since Trafalgar

During the fourteen or hours of action at Jutland, 8,500 men were killed on both sides. One was Alexander Kasterine’s sixteen year old great uncle Archibald, then servicing as a midshipman on new battle-cruiser, HMS Queen Mary (she’d only been in service three years). His eighteen year old brother Robert “Bertie” Dickson, his grandfather, was also in the battle and survived unscathed.

Bertie witnessed the main action through the periscope in his gun turret on the dreadnought HMS Benbow. In a series of letters between Bertie and his parents, kept in the archive of the National Library of Scotland, Alex learned of the horror and spectacle of battle, a young man’s pride at victory over the enemy, the parent’s and brother’s grief of losing the youngest member of the family, and a mother’s anger at the incompetence of a British Admiral.

Archibald and Bertie grew up in a comfortable and happy household in Edinburgh. Their father, William, was the Director of the National Library of Scotland, their mother, Kathleen, the daughter of General Murdoch Smith a Royal Engineer who had spent much of his life as diplomat in Iran overseeing the construction of railways and spying in the Great Game against Russia.

Family albums show photographs of the two boys with adoring parents and enjoying summer holidays fishing, tennis and beachcoming across Scotland. However, the boys were destined for early adulthood and at the ages of 12 were sent to Dartmouth Naval College to train as midshipmen.

Bertie (shown on the left) and Archibald Dickson together for the last day before they both returned to their ship before the Battle of Jutland, May 1916

In August 1914, their parents made the long journey to visit the boys at naval college. As they sat picnicking and watching a college cricket match, an officer ran onto the pitch announcing that Britain had declared war with Germany. The boys bid farewell to their parents and ran from the pitch to join their ships. They did not see Bertie for another two years, not till the eve of the Battle of Jutland.

Death in war is a lottery. Archie was sent to the battle-cruiser HMS Queen Mary, known as the “pride of the navy”. His older brother Bertie joined HMS Benbow a dreadnought battleship.

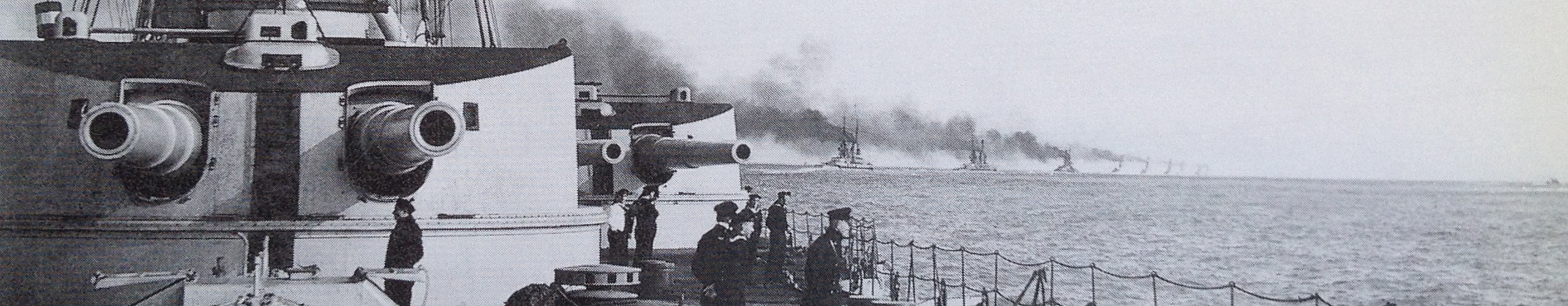

Bertie’s first sight of the battle was at the start of the second and heaviest engagement, just after 18:00, crouched inside one of Benbow’s gun turrets. Looking through his periscope he drew sketches of the battle and in a letter to his father, describes how saw the enemy coming into view at the same time as Vice Admiral Sir David Beatty’s Battle-cruiser Fleet. Bertie noted that he could not see his brother’s battle-cruiser, Queen Mary, that formed part of Beatty’s Fleet.

“The Battle-Cruisers were being straddled continuously, great columns of water rising all round them. We waited anxiously for a glimpse of the Queen Mary and Indefatigable, but they never came. They had gone before ever we arrived”.

Unknown to Bertie, an hour earlier, his brother Archie had been killed along with 1,285 other men when the Queen Mary was destroyed in the first phase of the battle. Another cruiser the Indefatigable was also destroyed in the same action with the German Scouting Group with the loss of 1,000 men.

Two days after the battle, Alex’s great grandparents received a telegram at their home in Gloucester Place, Edinburgh with the words “DEEPLY REGRET INFORM YOU MIDSHIPMAN ARCHIBALD W DICKSON KILLED IN ACTION + ADMIRALTY”.

Alex’s great grandmother, Kathleen, wrote to her only surviving son Bertie of her grief.

“My dearest and only boy, We can’t tell each other in writing what we are feeling today – my world was divided into three parts, or a third has crumbled away. You will, I hope, be some boy’s Father some day, but you can never be his Mother, so you can never know what I am feeling now.

I am telling the simple truth when I say, that all mothers and sons are not what we were to each other. He had needed me so much always, and I was perhaps too proud of the big handsome man my delicate kiddie was growing into. Thank God you missed being in the Queen Mary ”.

Archie and Bertie’s father, William Dickson, found some solace in what many considered at the time to be a victory for the Royal Navy, but the pain was acute for him too.

“It seems impossible to believe that we shall never see Archie again and that he, and his friends who used to come here, and that splendid ship of which they were all so proud, are at the bottom of the sea.

It is good to know from your letter and from all we hear elsewhere, that the results of the action have been so much better than appeared from the first news, and that all their sacrifices have not been in vain.

He quotes the reassuring words of a Commander Sands who had written to him to say

“you have at least the proud satisfaction of knowing that he fell doing his duty in a greater and perhaps more decisive action Trafalgar”

But that won’t bring Archie back. It is a terrible blow to Mum, but she is bearing it very bravely”.

Bertie wrote to his father, once it was confirmed that his brother was dead.

“The hardest truth is better than that awful uncertainty. I wonder if you saw him that last Sunday? I can picture it yet. I can’t realize coming home again and not finding Archie with you or at Rosyth. All our two lives we’ve been in a family of four and its heart breaking to think of all those happy holidays we’ve had and the home life that can never be the same again…In all the two years abroad last commission I never wanted to be home with you like I do now, but in all our troubles we must not think of our selves”.

By 4th June, Kathleen grief had turned to anger, specifically towards Vice Admiral Beatty.

“There is no end of a flowing account of the battle in the evening paper – it must be very badly informed, for if, as would appear from it, Beatty engaged the German Grand Fleet with his five Cruisers, for no better reason than to demonstrate British pluck, he would deserve to be shot.

Immediately after the battle, Archie’s grieving mother had asked his surviving son to write to the survivors to find out more about the circumstances of Archie’s death. Two of the 20 survivors wrote to Bertie, describing the likely last moments for Archie. Midshipman Jocelyn Storey was in “X” turret with Archie.

“At about 5.20 a heavy shell hit our turret and put the right gun out of action but killed nobody. Three minutes later an awful explosion took place which smashed up our turret completely. The left gun broke in half and fell into the working chamber and the right one came right back. A cordite fire got going and a lot of the fittings broke loose and killed a lot of people. Those of us who were left got open the cabinet door and got into the S. cabinet. I did not see any sign of your brother and don’t know what happened to him…whether he was killed by the explosion or the fumes I can’t say.

Storey was able to get out of the turret and sat on the side of the listing ship,

“where the after magazine went up and blew us into the water. When I came up the ship was gone and there were very few swimming in the water. I saw your brother nowhere….I think that is all I can tell you as I did not see him after the action started properly but just before he seemed quite happy not in the smallest degree”.

A month after the battle, Bertie wrote to his mother saying how he thought Archie met his end.

“I think myself that Archie was killed in the cabinet, knowing the construction of the 13.5” turret. I know that he was in the right hand corner of the cabinet, because he showed me his action station when I was onboard. Story say “the right gun came right back”, so one can well imagine the end.

How I wish someone had been saved who had seen him in those last moments before the ship sank, and who had spoken to him. But nobody need tell you that his last thoughts were of you and of home, and to no one who has fallen in this war have those thoughts been happier, more loving, or brought greater comfort”.

The second correspondent and surviving shipmate, Petty Officer Ernest Francis described to Bertie, the turret’s early success in the battle but also its last moments.

“We fires off 30 rounds and observes one of the German ships falling out of the line “First blood to Queen Mary”. Then came the big explosion, which shook us a bit … Immediately after that come what I term the big smash, and I was dangling in the air on a bowline, which saved me from being thrown down on to the floor of the turret. The turret was destroyed and the Lt gave the order to clear the turret.

Francis described what historians agree was the main cause of the Queen Mary and Indefatigable’s destruction.

“To finish my account, I will say that I believe the cause of the ship being blown up was a shell striking “B” turret working chamber igniting the shells stowed there in the ready racks, and the flash must have passed down into the magazine, and that was the finish”.

In one of the first engagements of the war, the Battle of Dogger Bank, a German ship, the Seydlitz, had nearly suffered the same catastrophic magazine explosion because its magazine was not protected from flash. The Germans immediately introduced modifications to their flash control ensure it did not happen again. The British navy did not make such changes.

The second reason for the Queen Mary and Indefatigable’s destruction was a tactical error by the British commander Beatty. Whilst subject to debate and controversy after the battle for several decades, modern historians agree that Beatty had made a fatal error in the battle.

Through poor communication he allowed his Queen Elizabeth class ships in the 5th Battle Squadron to become separated so that in the early stages of the action, these heavily armoured super-dreadnoughts were trailing behind, increasing the likelihood of British losses.

Beatty was also criticized for not firing at the German ships earlier enough and taking advantage of his ships greater range. At Beatty’s flagship, HMS Lion, was hit and fell temporarily out of line, the Derfflinger’s gunnery officer directed fire at the Queen Mary which was already being targeted by Seydlitz. After hits to its turrets from the two German ships, the ship listed to its port and a series of explosion destroyed the bow and stern. As men escaped the turrets and began to jump into the water, the ship exploded.

From the bridge of Lion, Beatty observed the 800 feet high explosion of fiery smoke that obliterated the Queen Mary. His Captain recalled that Beatty turned and remarked:

“There seems to be something wrong with our bloody ships today”.

Beatty and his remaining Battle-cruisers followed by the lagging 5th Battle squadron headed north and draw the pursuing German ships into the jaws of Admiral Jellicoe’s Grand Fleet who were steaming south toward Beatty. Communications from Beatty were again at fault as he gave incorrect information on his position so that as Alex’s grandfather on one of Jellicoe’s fleet’s ships observed

“…we sighted him half an hour before we expected to, and before the armoured cruisers had got into position”.

Despite this, Jellicoe quickly manoeuvred his fleet to port creating the first of two “crossed Ts” that meant the approaching German fleet was subjected to heavily concentrated British fire.

Beattie emerged from the gloom at great speed in what must have been a dramatic sight for the eighteen year old on Benbow.

“Led by the Lion, they (the British cruisers) suddenly burst through the mist on the starboard bow. Lion, Princess Royal, Tiger and New Zealand; they tore past us at full speed, their great funnels and superstructures silhouetted against the sheets of flare and thick cordite smoke as they fired salvo after salvo at the enemy whose flashes could now be seen in the distance between the ships. It was a wonderful sight. The Lion had been hit and was smoking forward. (Admiral) Beatty passed across the bows of the Battle Fleet and went right ahead of everybody….”

By 18:30 the two main fleets were heavily engaged. A few minutes later another line of British ships passed between the two fleets, as described by Bertie.

“(Admiral) Bobbie Arbuthnot was trapped on the weather side of the Fleet, and with his speed, was unable to follow the Battle Cruisers to the Van. He had no choice but to lead his squadron down our whole engaged side, between us and the enemy … He made a splendid fight of it, firing at a tremendous rate the whole time, but getting terribly mauled. At 6.20, just as he got on our starboard quarter, his flagship, the Defence, was blown to pieces by the most appalling explosion. She was turning, and a salvo hit her. A great flame shot up, followed by a pillar smoke and steam.

“All ships of both Fleets were firing now…The action had now become pretty fierce although the enemy’s firing from the time our Battle Fleet arrived became very poor indeed, in fact at times we wondered who they were shooting at. The fight developed on a roughly semi-circular course, with many alterations of course and speed. We were engaging both battleships and battle cruisers at a maximum range of about 16,000 yards. Four Kaiser class battleships were now plainly visible. Shortly after 630 a ship of this class was seen to haul out of the line badly on fire, turn over and sink. One enemy light cruiser with three funnels, although she may originally had four, drifted down disabled between the lines, burning fiercely”

As dusk fell at 18:46, the German fleet “altered course to starboard and disappeared”. Fearing torpedo attack and mines, Jellicoe did not pursue, a decision for which he was criticized by some for missing an opportunity to maul the enemy but praised by others as the enemy returned to its port where it stayed for the duration of the war. Pursuing the enemy was not necessary to achieve the same result and two years previously the Admiralty had agreed that the British fleet would not pursue the Germans in such circumstances.

However, fierce firefights continued during the night.

“An enemy’s battle cruiser now appeared on our starboard quarter. Some observers think it was a battleship of the Koenig class, but most agree now that it was the Lützow. Ranging commenced and at 19:17 we opened fire at 13,000 yds. We gave her five salvos of 13.5 lyddite of which the third took effect. A great flame shot up from her quarter deck, setting the after part of the ship on fire and she disappeared into the mist blazing”.

Bertie’s letter describes his dreadnought dodging torpedoes and thus gives an idea of why Jellicoe felt pursuing the German fleet would leave his fleet vulnerable to a destroyer attack.

“Endless forming and disposing began after this and for nearly an hour we did innumerable 9 pendant turns, increasing speed to 20 knots. At 8.30 the third and last destroyer attack was made by the enemy bearing NNW and this ship was very nearly sunk. We had to put the helm hard a port and stop the starboard engine to avoid a torpedo which passed immediately ahead. We replied with one rippling salvo of 6” which completely repelled them. These were our last shots. At 9.00pm we ceased fire, having been engaged intermittently for 2.5 hours, and the general action was broken off in the darkness and the mist which now came down thick and cold”.

The following day, Bertie’s ship searched for survivors.

“We passed through miles of oil and wreckage, and many dead bodies in lifebelts, but no sign of the enemy, except his submarines which were reported at 9,30 and which kept us on the jump for a little….

Later in the afternoon, the weather worsened and burials at sea took place

“The barometer had been low all day, but now it fell rapidly, and an icy wind accompanied by choppy seas came down on the Fleet. At 7pm all ensigns were half-masted while the bodies of men who fell in action in Barham and Malaya were committed to the deep. The seas were coming on boards some of the ships and spray was sweeping along the decks. Surely no men ever had a wilder burial”.

A week later, back in their base in Scapa Flow, a more formal burial took place

“Each ship sent 60 men and 4 officers. We formed up in a great long line inland from the sea. Then the Commander in chief and all the Flag Officers and their staffs passed silently up the line and headed by the massed bands of the Iron Duke, Benbow and Colossus, we marched slowly to the Dead March from “Saul” to the ground consecrated by the Archbishop of York and formed up in a great triangle, Admirals and their staffs in the centre. There must have been 3 or 4 thousand officers and men there”.

Whilst the British lost many more men and ships than the Germans, the battle was a victory in the sense that Admiral Jellicoe had forced the German navy back to its port where it remained for the rest of war, enabling a debilitating blockade of Germany.

Like thousands of other families, Alex’s great grandparents were left with only memories of their son. For Kathleen, she had a photograph developed that was taken on the boys’ last day together just before they sailed out of Rosyth.

Bertie wrote to his mother,

“I am so glad we had it taken, and we will value it more than any other, for it was taken less than 10 minutes before we said goodbye to Archie for the last time. I don’t know if you saw him again…but I never did… I do so sympathize with you carrying on your job in a house where every chair must bring back the dearest memories of Archie”.

Bertie served in the Navy for another 40 years until his retirement as a Rear Admiral. His mother grieved every 31st May at home in Edinburgh, inviting family friends to a shrine of flowers around a photograph of his midshipman son, a long way from the dark wastes of the North Sea where her son was lost.

(Courtesy of Alexander Kasterine)

SOME MORE STORIES :

Imperial War Museum HMS Benbow community :

https://livesofthefirstworldwar.org/community/2871