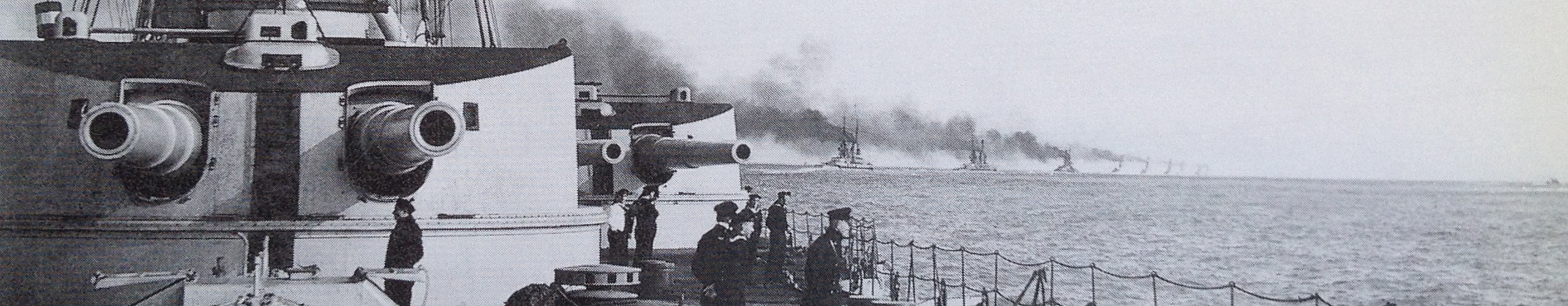

Two grandfathers at Jutland in the German Fleet. One a friend of Admiral Jellicoe’s from China Days.

From an interview with Jürgen Schultz-Siemens, one grandfather who was Max Schultz, the commander of the 6th Half Flotilla led by the V.41 at Jutland. He and my grandfather had fought together in China in 1900 and had, when they ran out of food, shared what little they had. When Jellicoe was in Berlin in 1913 for the marriage of the Kaiser’s daughter, he and Schultz met with their wives. On May 29th 2016, I was invited to the Commemoration service in the Wilhelmshaven Friedhof. With my cousin, I laid a wreath on Shlultz’s commemoration stone which is metres from the Lützow memorial.

Max Schultz’s memorial stone in the Wilhelmshaven Friedhof.

What is their role had in the events?

Leopold Siemens was Lieutenant and second radio officer on the battleship SMS Rheinland. Max Schultz, 13 years earlier entered the Navy, led the VI Half Torpedo boat flotilla as a Lieutenant Commander. He was of the attack against the British battle line which forced Jellicoe to turn away when Admiral Scheer wanted to withdraw theHigh Seas Fleet eleven torpedoes were fired though none hit. However, they achieved what they had set out to do. Force the British battleships to turn away. Schultz has received the Knight’s Cross of the Hohenzollern for his actions on the 5th June.

Max unfortunately died six months later off the Belgian coast when Flottillenführerboot, the V. 69 was sunk by British cruisers. He was among those who have not survive.

Max Schultz as Korvettenkapitän 1916.

But Jürgen knew his other grandfather, Leopold, who lived till after the second world war. He wants to write up his history for his own children with the memoirs that Leopold left.

Leopold was a radio officer and had to pass the commands from the flagship along the line as they were trying to get through the British line at night. The older officers looked down on the new technology of radio calling it Funkenpusterei . His ship, the Rhineland suffered two 15-centimeter hits and had ten dead. “Only the Stupid have no fear ,” he recalled later to Jürgen.

Max led torpedo boat at maximum speed, around 36 knots, right up to the British line. To within 6,000 meters. The sight of the firing British ships left an indelible impression: “sinister and gigantic”

Three grandsons meet. Richard Latham and Nick Jellicoe are grandsons of Admiral Jellicoe. Max Schultz’s grandson, Jürgen, stands between us his grandfather’s memorial stone in Wilhelmshaven.

Both officers felt they were part of an elite force. Well trained and prepared. They were aware of a certain superiority, because they knew British training well. They’d had such close contacts before the war. Both Leopold and Max saw how the German ships have achieved better shooting results. They both saw the terrible spectacle of the loss of three of the large British battlecruisers. They must have both felt proud, Jürgem says, despite them both also understanding that nothing had changed so far as the strategic position was concerned. The total blockade of Germany remained. They did not feel comfortable wearing their naval uniforms as time progressed. They felt they weren’t playing their part as so many of their friends were dying in the land war.

Leopold was a strong officer and proud of the care he felt for his men. ” Leadership and responsibility of people were the nicest thing about my job,” he said. He felt himself a Prussian and as “a convinced republican “. Like most officers in the imperial Navy he came from a bourgeois background. He stayed in the Navy and became a Vice Admiral in the Kriegsmarine and served with Karl Doenitz, He knew submarines well and became head of Submarine development. Tragically, he lost his only son Horst, my mother’s brother, as a young lieutenant on one of these is U -boats in 1942. Until the outbreak of war Leopold had served as Naval Attaché in London. He had very good and personal relations with the British Admiralty. The day Britain declared war on Germany, September 2nd 1939, he’d been invited by John Godfrey, head of the British Navy intelligence, to a dinner as the only foreign guest. No on spoke politics. Everyone knew what was about to happen. At the end of the evening he thanked Godfrey for his friendship and left with Warrender’s words of 1914: ” Friends today, friends forever .”

Leopold was dismissed in late 1944 as the naval commander in northern Norway and threatened with indictment for treason accused of not supporting the war effort vigorously enough.