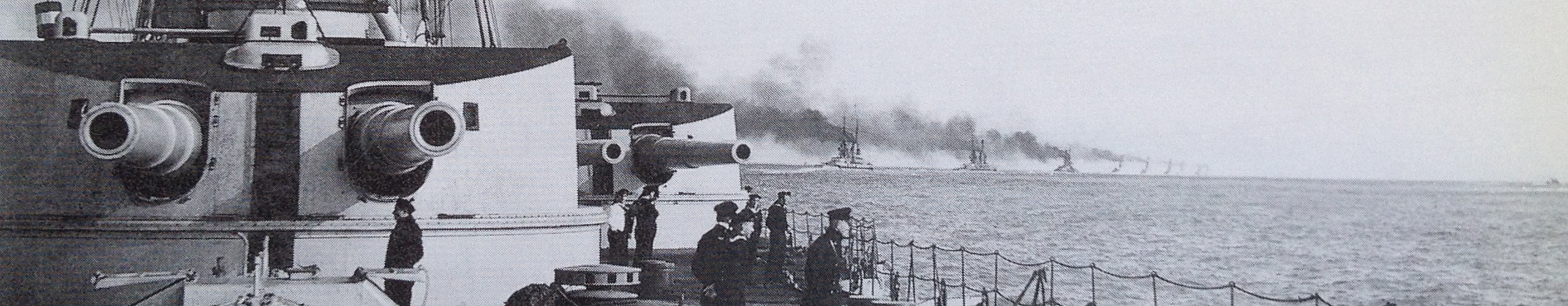

5.00 pm 31st May 1916

‘The hours of waiting seemed interminable. Our thoughts went home to those in happy ignorance of the coming fight. But there were the last minute preparations to make and the battle flags to hoist, which gave us a glorious thrill.’

The crew of HMS Spitfire of the 4th Destroyer Flotilla, Grand Fleet had been waiting months, years even, for ‘Them’ to come ‘Out’. They had been based at Scapa Flow since February 1915, waiting, and patrolling. Patrolling the Hoxa Sound, the Pentland Firth, escorting ships to Cromarty or Rosyth, screening the Battle Fleet out on PZ exercises, boarding merchant ships or fruitlessly searching for submarines and minelayers.

Spitfire on patrol, 1915

And occasionally proceeding at speed south toward Heligoland, or East for the Skaggerak on a ‘stunt’, hoping that there really was ‘something doing’ this time. A personal diary entry for April 1915 notes a busy morning watch with plenty of submarine screening etc.

« Met the Battlefleet at 4.00 am. We are steaming S50°E 15 knots which is straight for the Skaggerak. Nothing much happened all day. We all thought we might see something this time; so one can imagine how sick we were when at 6.0pm we all turned round ».[2]

The Spitfire officers would spend the long winter nights ship- visiting, dressing up to entertain, or quietly playing Bridge and Vingt John. In March 1915 they had purchased a monkey for the ship, arguing about where it would sleep (Captain’s cabin, eventually). In September a ping-pong tournament was organised and Spitfire lost to a combined Shark / Acasta team. Though very often the weather prevented any socialising so there was time to write a lot of letters, and wait for the mail.

Officers’ picnic – 30th May 1916

During the long summer days of 1915 officers of the Flotilla had taken to picnicking ashore, and Tuesday 30th May 1916 was no different – a picnic was arranged that day and officers from the Spitfire, Shark, Sparrowhawk, Ardent, Fortune & Acasta cooked up tea on a stony beach. But by that evening, at short notice, they were steaming out of a sunset, Eastward with the Battle Fleet; the Acasta and Shark detached to screen the three Battlecruisers, Spitfire and the rest of the 4th Flotilla screening the port wing of the Battle Fleet.

Through the night and into the next day, still Eastward and a little South, learning during the afternoon that the Battlecruiser Fleet were in action; gradually increasing speed towards the south, making them more certain that they should at last be in action.

« Now we heard the sound of guns, and flashes on the horizon. » [1]

They were ordered to get ahead of the deploying Battle Fleet as they were on the Fleet’s disengaged side. The wakes of so many vessels going at full speed close beside each other caused the most curious breakers.

These were occasionally mistaken for the signs of submarines, and a good deal of firing took place away behind them. Presently, the destroyer Acasta came hurtling right across the track of the Fleet. She was flying ‘not under control’ signals.

« Her crew were all cheering hard, and we cheered back, and [we] cheered again as we saw the bow and stern of a big ship sticking up out of the water. But our cheers ceased suddenly as we read the name Invincible on the stern portion ». [1]

Torpedo practice – 1915

They were now ahead of the Battle Fleet awaiting orders, knowing that they may be ordered to deliver, or repel a torpedo attack at any moment. Shot was falling within sight though not reaching them and all the while watching, and waiting. Visibility was worsening due to smoke from gunfire, mist and enemy smokescreens. And by dusk they could hear only sporadic salvos, ahead and behind them.

Windy Corner, Jutland – WL Wyllie

At 9.30pm they were forming up 5 miles astern of the Battle Fleet. They did not know the outcome of the battle, where the enemy were or even where most of their ships were – only that they should form 5 miles astern of the Battle Fleet. By 10.00pm they were settled in line ahead – Tipperary leading, Spitfire, Sparrowhawk, Garland and Contest of the 1st Division following.

It was a very dark night as there was no moon, and the sky was overcast and the atmosphere hazy.[3]

They were very nervous of running into their own ships by mistake and had been ordered to keep a sharp lookout for the enemy. In the darkness they could make out ships closing them from astern, Tipperary made the challenge; they were British. Shortly before midnight they saw again the dark shape of a line of ships on their starboard quarter, occasional glare in their funnel smoke. Some thought they were friends, but they could just as well be the enemy, so 21” torpedo tube and 4” gun were kept trained on them. Maybe it reminded them of a patrol in early 1915 where it was moonlight. The St Vincent came out – we could have got in a lovely shot with our mouldies, about 8000 yds – she never saw us till we challenged her.

But here visibility was under 1000 yards and when the dark outlines were nearly abeam, at a range of between 500 and 700 yards Tipperary again made the challenge…

The reply was all three ships switching on a blaze of searchlights. The majority of these lights were trained on the Tipperary and only a few stray beams lit on us and on our next astern. Then these lights went out, and after an extraordinarily short pause were switched on again, and at the same moment a regular rain of shell was concentrated on our unfortunate leader, and in less than a minute she was hit and badly on fire forward. [2]

« At the same moment we fired our 2 torpedoes and saw one of them hit. But I saw the most infernal storm of shells hitting the water just ahead of us, and all around the Tipperary ». [1]

« [We] had been hit several times. The after guns’ crew and the torpedo party were suffering the most casualties, but the latter luckily not until after they had fired our second torpedo, from the foremost tube ». [2]

« Hours and years of practice took over and immediately both torpedoes were fired the Spitfire turned away, helm put hard-a-starboard, increasing to full speed and away out of it. It was at that moment they were hit amidships by a full salvo, and seemed to disappear, one great sheet of flame. But they got safely away and with two torpedoes gone the question was, at whom to fire the spare torpedo? That was soon solved as soon as we resumed our course, we saw Tipperary behind us, a dreadful, burning torch. She was stopped and being fired at under the concentration of the enemy’s searchlights. So back we went to attack the ships attacking her ». [1]

But they could not load the spare torpedo due to damage sustained to the loading gear; the Torpedo Gunner was injured and the majority of the torpedo ratings were either injured or killed. The Captain decided to go to the assistance of the Tipperary and, if necessary, carry on action with their guns. As they got near he felt maddened at seeing their leader disabled and being so fiercely attacked. He gave what seemed the hopeless order to fire at searchlights, which, as if at target practice, winked, and went out.

« We closed the Tipperary, now a mass of burning wreckage and looking a very sad sight indeed. At a distance her bridge, wheel-house and chart-house appeared to be one sheet of flame, giving one the impression of a burning house, and so bright was the light from this part that it seemed to obliterate one’s vision of the remainder of the ship and of the sea round about, except that part close to her which was all lit up, reflecting the flames ». [2]

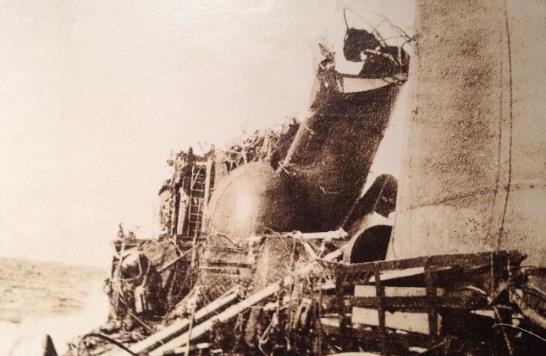

« But the Germans were still very close, and even without searchlights the Spitfire was visible. To the horror of the Captain a large German ship had altered course to ram them. He had a choice – either turn to port onto a similar course and suffer the fate of the Tipperary – continue on the same course and be cut in two – or turn to starboard towards them and trust to luck. He chose this last, and they turned at high speed, but, oh! how slowly we seemed to come round. Everything was lit up by the burning Tipperary. As the enemy loomed nearer and nearer it seemed impossible that we could get clear… [on] the bridge we were blinded by the flashes of our fo’c’sle gun ». [1]

and with a ghastly, fearful crash the two ships met port bow to port bow. In the glare of searchlight men were hurled across the deck and one man from the fo’c’sle gun’s crew was lost overboard. The ship rolled like she had never rolled before and the sides of the two vessels bumped and ground together, ripping plate and scuttle. When they were bridge to bridge the German fired her forward main armament probably 11”, point blank at us. The shell passed over my head and through the bridge. The blast was terrific [3] and reduced the bridge to a mass of tangled wreckage. The projectiles themselves did not detonate, but as they passed through they decapitated one man, and cut another in two, either side of the Captain. The Captain himself was thrown by the blast 24 feet onto the upper deck, face down with his head over the side, unconscious. The rest of the bridge personnel were killed or wounded by concussion.

The huge German ship « surged down our port side, clearing everything before her; the boats came crashing down and even the davits were torn out of their sockets, and all the time she was firing her guns just over our heads ». [2] But none of the shells seemed to hit. And all the while the German vessel kept the Spitfire illuminated until finally clearing her astern. Spitfire was left afloat, but drifting in a somewhat pitiful condition.

« …fires started breaking out forward, and to make matters worse all the lights were short- circuited, so that anyone going up to the bridge received strong electric shocks. Moreover, all the electric bells in the ship were ringing, which made things feel rather creepy ». [2]

The Captain could not be found, so the 1st Lieutenant took command. His two concerns were to regain control of the ship and put out fires that might draw unwanted attention.

The moment of collision. The 935 ton Spitfire rams into the 20,000 ton SMS Nassau.

It was extraordinary the way fire spread, burning strongly in places where one thought there was hardly anything inflammable, such as on the fore-bridge and the decks, but flags, signal halliards, and the coco-nut matting on the deck all caught fire, and sparks from the latter were flying about everywhere. [2]

A large-calibre shell had grazed the deck and the bottom of the second funnel. A second fire was spouting from the hole and stokers beneath in the foremost boiler-room had to don gasmasks. Many of the fire hoses were cut by splinters and useless so it took time to get these fires under control.

One got rather a nasty shock by walking one moment on a small fountain from the fire main and the next minute stepping on something smouldering or burning. [2]

An inspection of the engine-room and boiler-rooms found that three of the four boilers were functioning and that the ship was capable of 6 knots. And as the bridge had been destroyed a voice- pipe was rigged to the engine-room from the compass aft, and for about half an hour they steered by that. They had noted their course of NW shortly before the collision, however, they had no Coxswain and the two Quartermasters were injured, one in the right hand, one the left; but they took charge of the wheel – one ‘Navy Pattern Quartermaster’ as Rudyard Kipling later put it.

The Captain, Sub, Gunner, Coxswain and Chief Stoker were all missing – the latter was found with a broken jaw under the Downton pump, and the Coxswain, delirious, under the remains of his wheel. He was got out, but an Able Seaman also on the bridge was trapped and had to have his leg amputated, in the dark, with no anaesthetic.

The Chief Stoker found the semi-conscious Captain, lifting and moving him to the midship gun. Still dazed, the Captain angrily demanded to know why they weren’t firing whilst the Sub and Gunner also reappeared, fortunately not badly injured. The majority of the crew were now aft having misunderstood the order ‘connect up aft’ and saw on their starboard quarter, a few hundred yards away what appeared to be a German battlecruiser, on fire, steering as if to cut them in two, and we thought we were done for; I believe the majority of us lay down and waited for the crash. But no crash came. To our intense relief she missed our stern by a few feet, but so close was she to us that it seemed that we were actually lying under her guns, which were trained out on her starboard beam. She tore past us with a roar, rather like a motor roaring up hill on low gear, and the very crackling and heat of the flames could be heard and felt. She was a mass of fire from foremast to mainmast, on deck and between decks. Flames were issuing out of her from every corner…[2]

With the ship now under control and the majority of the crew accounted for a ‘council of war’ was held. The breaking dawn was about to show in greater detail the extent of the damage:

The damage on the Spitfire was extensive

The main concern was the damage to the bow – a huge, lengthways gap of about 60 feet. Attempts were made to shore this with whatever was to hand but any shoring was washed away time and time again. Mess, shell and storerooms forward were flooded or unreachable causing concern bulkheads would not hold. All three 4” guns however were found to be undamaged and crews found for them. And they were finally able to load the spare torpedo.

With the galley being undamaged they had some food, a cup of cocoa and a tot of rum was served to the men which cheered them up no end.

« I shall never forget that early morning cup of cocoa. We officers all muffled up, grimed and hollow-eyed, were seated on the ammunition sacks, sheltered by what remained of the canvas protection to the steering-wheel… »[1]

Captain Trelawny (right) drinking hot cocoa the morning after

They found their Union Jack amongst the wreckage – the White Ensign with its shrapnel holes, was still flying. After a grisly search they then buried their dead; with all hands again aft the Captain read the funeral service. The colours under which they had fought were half- masted, and we lowered their bodies as reverently as we could into the deep; there was a big sea running. Then we turned to and cleared up the ship. [2]

« Another concern was their being able to reply to any challenge as radio, searchlight, mast and flags had all been blown away. They cut up remaining flags to denote who they were and flew them at an improvised mast. For night, they had recourse to an electric torch. Navigation was similarly difficult – a torn piece of a chart was found and a book-case batten used as a ruler as (my) chart and navigating notebook were lost, so that I was not certain of our position. For the North Sea is a large place, although one always pictures it to oneself as being so small ». [3]

The original intention was to make for Harwich; but as wind and sea rose they were forced gradually northwards. They took position and directions from a Norwegian merchant ship, following its wake for a time as they assumed that would lead them towards the English coast; but again the weather edged them northward as they attempted to protect their damaged bow. The wind still increased to a gale and at 1.00 am it was decided there was little choice but to fire distress signals. They got the box of ‘fireworks’ up and sat on them, unable to quite bring themselves to use them. But with dawn breaking for a second time, as if, it seemed to them, by a miracle, the wind moderated and the sea became smooth finally enabling them to make 10 knots. After meeting some minesweepers they made landfall about 20 miles from the Tyne, and refusing to take a tug – the two Quartermasters still at their posts after 36 hours, guided the ship between the piers at about noon 2nd June.

Spitfire arrives back near the Tyne

11.0 pm 31st May 1916

« The course laid down for our Flotilla was to meet with the heaviest part of the German line: our four leading destroyers were shortly to engage not only with cruisers but with dreadnoughts. But nobody knew. » [1]

Lt Cdr CWE Trelawney [1] Lt AP Bush[2]_Sub Lt Wiggins[3]

(The account of HMS Spitfire at Jutland is courtesy of Alan Bush, grandson of Lt. Athelstan P Bush)

SOME MORE STORIES :

Imperial War Museum HMS Spitfire community :

https://livesofthefirstworldwar.org/community/2578